What I Wish I Knew Earlier About Retirement Risks in Senior Education

Planning for retirement while investing in senior education can be a smart move—but it’s packed with hidden risks few talk about. I learned this the hard way, balancing financial security with lifelong learning. Many assume further education at this stage is low-risk, but without proper planning, it can strain savings and delay financial freedom. This is a real talk about spotting those risks early, protecting your nest egg, and making informed choices that truly pay off. The dream of learning something new in midlife or beyond—whether it’s coding, financial planning, or wellness coaching—can feel empowering. But when that dream comes with tuition bills, time commitments, and uncertain outcomes, it becomes more than a personal decision. It becomes a financial one. And like any financial decision, it requires clarity, discipline, and a clear-eyed view of both rewards and risks.

The Growing Trend of Lifelong Learning in Retirement Planning

In recent years, more adults aged 50 and older have returned to classrooms—not to finish degrees they left behind, but to prepare for what comes next. This shift reflects a broader change in how people view retirement. No longer seen as a finish line, retirement is increasingly viewed as a phase of reinvention. With longer life expectancies and evolving job markets, many are choosing to extend their working years, pivot into new fields, or start small businesses. Education plays a central role in these transitions. Community colleges now report rising enrollment among older students, and online platforms like Coursera, edX, and LinkedIn Learning have seen increased participation from the 50-plus demographic.

What’s driving this trend? For some, it’s the desire to stay mentally sharp and socially engaged. Studies show that continued learning supports cognitive health and emotional well-being in later life. For others, the motivation is financial. A growing number of retirees or near-retirees are investing in training programs that promise higher income potential, whether through freelance work, consulting, or launching a service-based business. Certifications in areas like project management, digital marketing, or financial advising are particularly popular. These credentials are seen as gateways to flexible, well-paying opportunities that fit into a semi-retired lifestyle.

Yet, behind this positive narrative lies a financial reality often overlooked. While education can open doors, it also comes with costs—both monetary and temporal. Tuition, books, software subscriptions, and even the cost of a dedicated workspace add up. More importantly, time spent learning is time not spent earning, volunteering, or resting. For those already managing fixed incomes or drawing down retirement accounts, these trade-offs can be significant. The decision to pursue education is no longer just about personal growth—it’s about how that choice fits into a broader financial plan. Without careful evaluation, what begins as a step toward empowerment can become a strain on long-term stability.

Why Senior Education Isn’t Just a Personal Choice—It’s a Financial Decision

When a 30-year-old invests in education, the expectation is clear: higher earnings over a longer career. But for someone in their 50s or 60s, the timeline is compressed. Every dollar spent and every hour invested must be weighed against the shrinking window for financial recovery. This changes the calculus entirely. Education at this stage isn’t just a personal development expense—it’s a financial decision with direct implications for retirement security. The cost of a certificate program may seem modest on its own, but when pulled from a retirement account or funded with credit, it can delay financial independence by months or even years.

Consider the opportunity cost. Time is one of the most valuable assets in retirement planning. An individual spending 15 hours a week on coursework over six months is giving up the chance to earn income through part-time work, consultancies, or even paid caregiving roles. For those who rely on seasonal or gig-based income, that lost time can mean a noticeable dip in annual cash flow. Additionally, some programs require internships or capstone projects that offer no pay, further reducing earning potential during a critical phase of wealth preservation.

Then there’s the question of return on investment. Not all education leads to higher income, especially in saturated markets. A certificate in social media management might help one person land freelance clients, while another finds the market too competitive to generate consistent work. The financial benefit depends on multiple factors: the individual’s prior experience, local job demand, networking ability, and marketing skills. Without a clear path to monetization, education risks becoming a well-intentioned expense with little financial payoff. That’s why treating education as a financial asset—or liability—is essential. If it increases earning potential or reduces future expenses (such as health-related costs through preventive care training), it may be worth the investment. But if it’s pursued solely for emotional satisfaction without a financial plan, it can quietly erode retirement readiness.

Hidden Risks Most Overlook in Late-Career Education

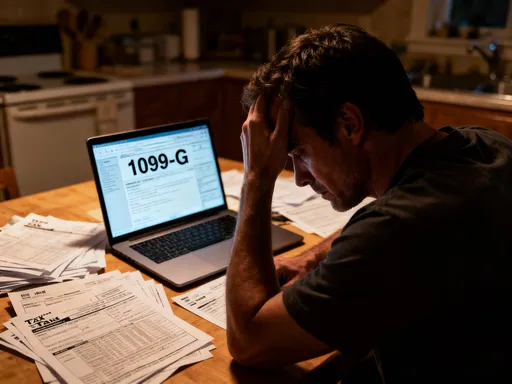

Many people enter educational programs with optimism, assuming that completing a course will naturally lead to new opportunities. But the reality is more complex. One of the most common yet overlooked risks is overspending on programs with little proven return. Some for-profit institutions market heavily to older adults, emphasizing transformation and success stories without disclosing actual job placement rates or average earnings of graduates. Individuals may pay thousands for training in fields like holistic wellness, real estate investing, or tech support, only to find that the market is oversupplied or that additional licensing is required to work legally.

Another hidden risk is underestimating the time commitment. Adults in midlife often juggle multiple responsibilities—family, caregiving, part-time jobs, and health management. Adding a rigorous course load can lead to burnout or force trade-offs in other areas. Some learners drop out midway, having spent money and time without gaining a credential or usable skill. Others complete programs but struggle to apply what they’ve learned due to lack of practice opportunities or outdated curriculum. Emotional motivations also play a role. Fear of becoming obsolete in a fast-changing world, or pressure to keep up with peers, can push individuals into decisions they haven’t fully evaluated. The desire to feel relevant or capable is powerful, but when it overrides financial prudence, it can lead to regret.

Debt is another serious concern. While younger students may take on loans with the expectation of decades of future income, older adults have fewer years to recover financially. Taking on debt for education at 58 means repayment coincides with retirement, potentially reducing disposable income during a phase when fixed costs like healthcare are rising. In some cases, individuals have drained emergency savings to pay for training, leaving them vulnerable to unexpected expenses. A medical bill or home repair can become a crisis if there’s no buffer. These risks are rarely discussed in promotional materials, but they are real and significant. The key is not to avoid education altogether, but to approach it with the same caution used when evaluating any financial investment.

Spotting Red Flags: How to Evaluate Programs Before You Invest

Not all educational opportunities are created equal, and some carry more risk than others. The first step in protecting your finances is learning how to evaluate programs critically. Accreditation is a basic but essential filter. Programs offered by regionally accredited colleges or universities are more likely to meet quality standards and offer transferable credits. In contrast, many private training schools operate with minimal oversight and may not be recognized by employers or licensing boards. Always verify the accrediting body and ensure it’s legitimate and respected in the field.

Next, look at outcomes. Reputable institutions often publish job placement rates, average starting salaries, and alumni success stories with verifiable details. If a program can’t provide this information or offers only vague testimonials, that’s a red flag. Ask to speak with recent graduates, if possible, and inquire about their actual experiences finding work or applying their training. Be cautious of high-pressure sales tactics. Some providers use limited-time discounts or fear-based messaging—“You’ll be left behind if you don’t act now”—to push quick enrollment decisions. These tactics are designed to bypass careful thinking and can lead to rushed financial commitments.

Cost transparency is another critical factor. A clear breakdown of all fees—tuition, materials, technology charges, and certification exams—should be available upfront. Hidden costs can turn an affordable program into an expensive one. Also, consider the format. Online programs offer flexibility, but not all are self-paced. Some require live sessions or strict deadlines that may conflict with personal schedules. Look for options that allow auditing or trial periods, so you can assess the quality before committing fully. Finally, research whether the credential leads to recognized certifications or licenses. In fields like healthcare, finance, or education, proper certification is often required to work legally. Without it, even the best training may not translate into income.

Balancing Risk and Reward: When Education Makes Financial Sense

Despite the risks, there are clear scenarios where senior education can enhance financial security. The key is alignment—between the program, the individual’s goals, and the market demand. For example, training in high-demand fields like cybersecurity, telehealth support, or renewable energy installation can open doors to well-paying contract or part-time roles. These industries are growing and often value experience over age, making them accessible to older adults with transferable skills. Similarly, certifications in financial literacy, elder care planning, or mediation services can be leveraged into consulting practices that serve aging populations—a market that is expanding rapidly.

Another smart path is education that reduces future expenses. Courses in nutrition, stress management, or chronic disease prevention can lead to healthier lifestyles, potentially lowering healthcare costs over time. While these benefits are harder to quantify, they contribute to long-term financial well-being by reducing the need for expensive medical interventions. Similarly, learning home maintenance, energy efficiency, or basic repair skills can save thousands in service fees and utility bills. These are forms of education that pay off not through income, but through savings—a crucial aspect of retirement planning.

Freelance and gig economy skills also offer strong potential. Platforms like Upwork, Fiverr, and TaskRabbit allow individuals to monetize skills in writing, graphic design, virtual assistance, or tutoring. Short, targeted courses in these areas—especially those with portfolio-building components—can yield quick returns. The best outcomes occur when learning is specific, affordable, and directly tied to a monetizable skill. For instance, a four-week course in resume writing followed by joining a freelance platform can generate income within months. The financial logic is clear: low upfront cost, short time commitment, and a direct path to clients. These are the kinds of education investments that support, rather than threaten, financial independence.

Protecting Your Retirement: Risk Mitigation Strategies

Once you’ve decided to pursue education, the next step is protecting your financial foundation. The most effective strategy is setting a strict budget. Determine in advance how much you’re willing to spend—and stick to it. This includes not just tuition, but all associated costs: books, software, internet upgrades, and even transportation if in-person classes are involved. Treat this budget like any other financial goal, such as saving for a vacation or home repair. If the total exceeds your limit, look for lower-cost alternatives or delay enrollment until you’ve saved enough.

Whenever possible, use tax-advantaged accounts wisely. While traditional retirement accounts like IRAs and 401(k)s are not designed for education expenses, some individuals consider early withdrawals to fund training. This should be done with extreme caution, as it can trigger penalties and taxes, and reduce long-term savings. A better option may be to use a Roth IRA, where contributions (but not earnings) can be withdrawn penalty-free for any reason. However, this should only be considered if the potential return justifies the risk and if emergency funds remain intact.

Start small. Instead of enrolling in a full program, begin with a single course or audit option. Many colleges and online platforms allow learners to sit in on classes without paying full tuition or earning credit. This lets you assess the quality, workload, and relevance before making a larger commitment. It’s a low-risk way to test the waters. Additionally, maintain your emergency fund throughout the process. Do not dip into savings meant for unexpected expenses. If education costs require reallocating funds, do so from discretionary categories—like travel or dining—not from reserves.

Finally, build in regular financial reviews. Every three to six months, assess your progress: Are you gaining useful skills? Is the program leading to tangible opportunities? Is your budget still on track? If not, be willing to adjust or exit. Flexibility is a strength, not a failure. The goal is not to complete a program at all costs, but to make choices that support long-term financial health. Insurance and income protection also play a role. If you’re relying on part-time work to fund education, consider disability or income protection policies that can cover lost earnings due to illness or injury. These safeguards ensure that one setback doesn’t derail your entire plan.

Building a Smarter Future: Lessons That Go Beyond the Classroom

The journey of pursuing education in later life offers lessons that extend far beyond the curriculum. It teaches patience—the understanding that meaningful change takes time. It highlights the danger of impulsive decisions driven by fear or social pressure. And it reveals the power of informed risk-taking: moving forward not because everyone else is, but because you’ve weighed the costs, understood the odds, and chosen a path aligned with your values and goals. True financial wisdom isn’t about avoiding all risk—it’s about choosing which risks are worth taking.

For seniors considering education, the most valuable asset isn’t just knowledge, but perspective. You’ve lived through economic cycles, career shifts, and personal challenges. That experience gives you an edge in evaluating opportunities with clarity and calm. You know that not every trend is worth following, and not every promise is trustworthy. By applying that wisdom to your financial decisions, you can pursue learning that enriches your life without compromising your security.

Ultimately, the goal is balance. Education can be a powerful tool for growth, connection, and even income in retirement. But it must be approached with the same care as any major financial decision. By identifying risks early, setting clear boundaries, and staying focused on long-term stability, you can make choices that pay off—not just in skills learned, but in peace of mind gained. That’s the kind of return that no certificate can measure, but everyone can feel.